Hatshepsut and Nefertiti: Two Women Who Changed Egypt

This Collection Highlight is adapted from the spotlight exhibit ‘The Women Who Changed Egypt’, which opened at the Egypt Exploration Society in May 2025.

Introducing Hatshepsut and Nefertiti

It is often assumed that women in the past held little influence and had no place in public life. This was certainly not true in ancient Egypt; the Nile Valley was home to many powerful women who shaped society during their own lifetimes and for the generations that followed.

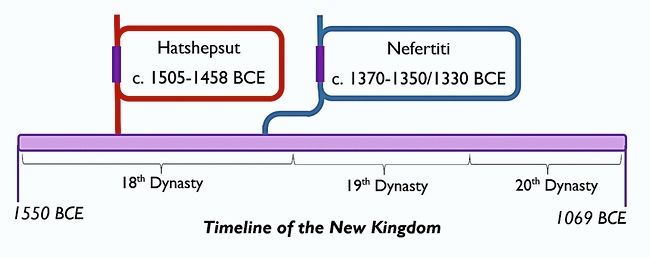

Two famous examples of such women lived during Egypt’s New Kingdom, in the period known as the 18th Dynasty (c. 1550-1292 BCE). Hatshepsut and Nefertiti were female rulers who achieved remarkable feats during their lifetimes. Despite ancient efforts to erase them from history, we still remember their names over 3,300 years later.

Negative showing a stone fragment inscribed with an image of Akhenaten offering incense to the sun god Aten, who takes the form of a solar disk with hands at the end of its rays (TA.NEG.22.067). From the 1921-22 excavations at Amarna.

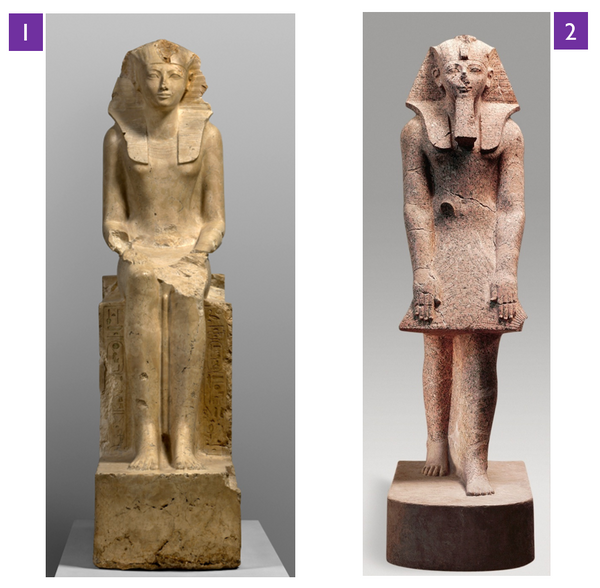

Expressions of Power

A range of methods were used to communicate the power and influence of these women.

Hatshepsut used different titles to convey her evolving status. Below are drawings from the EES archive showing two small inscribed plaques, discovered during the Society’s excavations at the site of Deir el-Bahari. The first (EES 141) may date to Hatshepsut’s time as queen regent, since it records only her birthname alongside the important priestly title ‘god’s wife’. The second (EES 106) is shaped like a cartouche and carries Hatshepsut’s throne name ‘Maatkara’ (left) as well as her birthname (right), so can be dated to her reign as king.

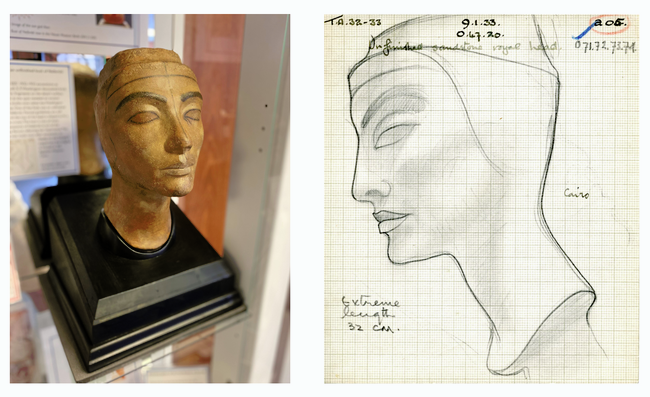

Nefertiti’s importance is clear from how prominently she features in art of the Amarna Period. A historic replica in the EES collections represents an unfinished bust of Nefertiti discovered during the Society’s 1932-1933 excavations at Amarna; the original is housed in the Egyptian Museum Cairo. Painted guidelines are still visible and the top of the head is shaped to fit a separate crown.

Left: The EES' historic replica of the unfinished bust of Nefertiti.

Right: Object card recording the bust as discovered during the Society's 1932-1933 Amarna excavations (TA.OC.32-33.205).

Impacts and Achievements

Both Hatshepsut and Nefertiti achieved great feats in areas such as monument building, international relations, and religion.

Hatshepsut did everything that was expected of a king. She appears to have led a foreign military campaign, and built impressive monuments across Egypt and Nubia, including her famous memorial temple at Deir el-Bahari where the EES conducted extensive excavation and documentation work. The temple contains scenes depicting a trading expedition to the distant land of Punt, believed to have been located in the Horn of Africa. The watercolour below (ART. 219) was made by Rosalind F. E. Paget in 1897 and records a fragment from the Punt scenes, featuring baboons, cattle, an incense tree, and a giraffe. The success of Hatshepsut's kingship may have been important to Nefertiti some 100 years later; an alabaster jar from the reign of Hatshepsut was discovered at Amarna during the Society's 1931-32 excavations, perhaps brought to the new city as an heirloom of her reign. A replica of the vase is held in the EES archive (see below).

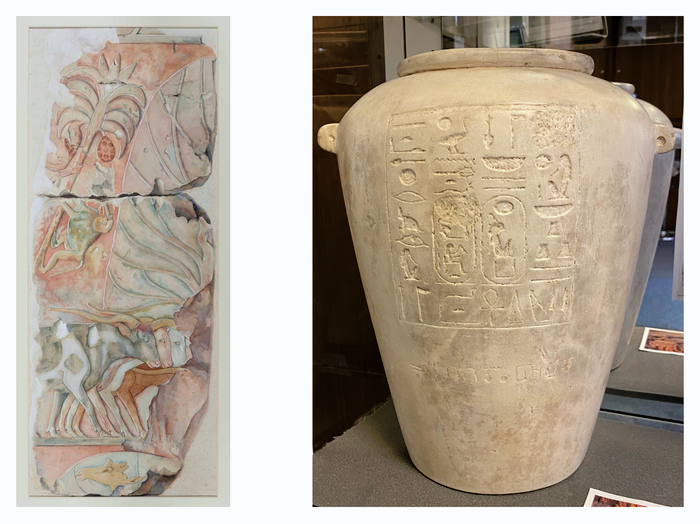

Left: Watercolour by R. F. E. Paget depicting a scene of Punt from the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari (ART.219).

Right: Historic replica of an alabaster vase inscribed with the kingly names and titles of Hatshepsut, discovered at Amarna. The name of the god Amun has been erased from the inscription, part of Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s persecution of Amun in favour of Aten.

Nefertiti was central to the creation of the city of Amarna, whose ancient name was Akhetaten, meaning ‘Horizon of the Aten’. This new capital was the centre of the Aten cult, where she and the king regularly performed rituals in the city’s temples which were open to the sky. Yet Nefertiti’s influence also extended beyond Amarna. An Atenist structure called the Hut-Benben (‘mansion of the sunstone’) was built at the Karnak temple complex in Thebes. The decoration on the remaining blocks depicts Nefertiti as the primary conductor of ritual in the building, an extremely rare position for royal wives to hold in temple iconography.

Negative showing a view over part of the site of Amarna, taken during the Society's 1930-31 season.

Erasing Women

Despite their impressive achievements, both these women became targets of attempts to obliterate their memory.

After Hatshepsut died, her former co-regent Thutmose III oversaw a campaign to erase her name and image. It has long been assumed that these attacks were motivated by vengeance for usurping Thutmose’s place on the throne. However, more recent work (such as that of EES Centenary Award holder Jun Yi Wong) has shown the situation was likely more complex, with erasures only beginning some 20 years after Hatshepsut’s death.

Over 100 years later, Nefertiti and Akhenaten’s ‘revolution’ came to an end. The cult of the Aten was never popular outside of elite circles and may have stoked anger for both religious and political reasons. Following Akhenaten’s death and a few other short reigns―Nefertiti herself may have briefly ruled as a king―the city of Amarna and Atenist monuments elsewhere in Egypt were torn down. The names and faces of Akhenaten and Nefertiti were smashed or chiselled away in hope that the couple would be obliterated in this world and the next.

From a negative taken in the Royal Tomb at Amarna during the 1934-35 season (TA-RT.NEG.34-35.028). The image shows a figure of Nefertiti, whose face has been erased.

Even in the face of efforts to erase them, Hatshepsut and Nefertiti have become some of the most famous names from the ancient world, due in part to the work of the Egypt Exploration Society. The documents, photographs, and artworks held in the EES archives help to reveal the stories of these remarkable women and safeguard them for generations to come.