Analysing the destruction of Hatshepsut’s monuments

In 2020, the Society awarded Jun Wong (University of Toronto) a Centenary Award to explore patterns of destruction at monuments constructed during the reign of Hatshepsut. On the left is Jun photographing scenes at the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. The Society is particularly grateful to Prof Pearce Paul Creasman (Director of the American Center of Oriental Research) for providing free accommodation for Jun during his research visit at Wilkinson House. Read more about Jun's project below.

Photos: PCMA UW Deir el-Bahari Temple of Hatshepsut Project/Jun Wong

The destruction of Hatshepsut’s monuments has long intrigued scholars. Perhaps due to preconceptions regarding her gender, early studies tend to interpret this as the result of intense animosity by Thutmose III. Although recent findings have provided a healthy correction to this view, few studies have examined this phenomenon in an extensive manner. This project aims to systematically document and analyse the erasures found on Hatshepsut’s constructions, in order to gain a better understanding of the motivations and ideologies behind them.

The vast majority of Hatshepsut’s monuments have complex histories that extended far beyond her reign. For instance, many were subject to attacks during the Amarna period, before being restored by subsequent rulers. Like other Pharaonic monuments, most of them were also targeted by iconoclasts following the advent of Abrahamic religions.

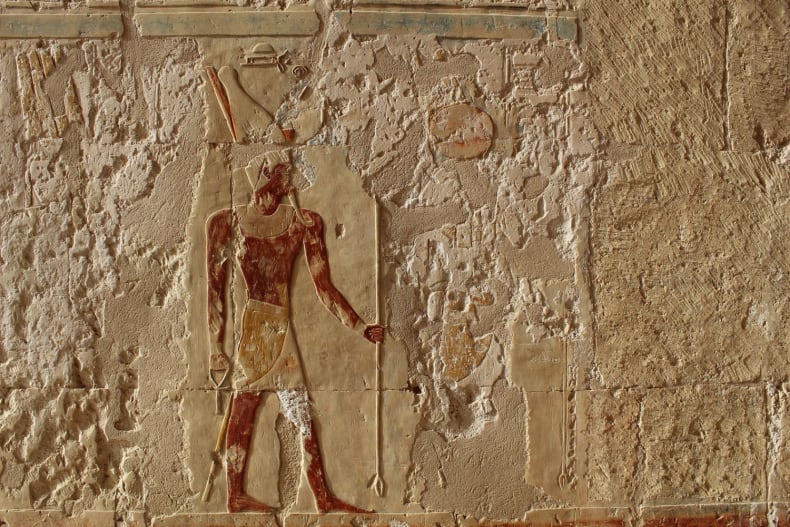

On this scene from Deir el-Bahri, the god Atum has been spared from attacks by Akhenaten’s followers, whereas the deities on either side have been restored in sunk relief. The sun-disc that formed the crown of the rightmost figure has also been spared by followers of Akhenaten.

As a result, each scene on Hatshepsut’s monument tends to present an intricate ‘stratigraphy’ of its own: parts of the scene may be carved, re-carved, hacked out or plastered at various points; making it challenging to discern their relative chronology. Moreover, well-executed alterations can be mistaken as the original decoration, with only slight discrepancies in relief depth revealing otherwise. In areas that are poorly illuminated, these subtle differences can be tricky to identify.

A restoration text of Ramesses II is superimposed on this scene, which has been thoroughly erased after the reign of Hatshepsut.

The distinction between texts in the original raised relief (right) and the restoration in sunk relief (left) becomes apparent under favourable lighting conditions.

Each episode of destruction also presents its own nuances: the erasure of Hatshepsut’s cartouches, for instance, are often only executed partially; indicating a reverence to Amun and Re, who formed part of her nomen and prenomen. Other cartouches, however, could be re-inscribed with the name of her predecessors, or left completely unscathed. Following the documentation process, these variations will be analysed quantitatively to reveal underlying patterns.

Left: The feminine endings referring to Hatshepsut have been chiseled out.

Thanks to the support of the Egypt Exploration Society's Centenary Award, I was able to begin documenting in the Middle Portico of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, which includes the well-known scenes detailing her divine birth and the expedition to Punt. The documentation was conducted as part of the Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission at the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. Eventually, the project will expand to other major constructions of Hatshepsut at Karnak, Speos Artemidos, and into Sudan.