Rehousing the Abydos and Armant Glass-Plate Negatives

by Stephanie Boonstra

The EES’ Lucy Gura Archive contains a vast array of materials generated from the Society’s nearly 140 years of excavating in Egypt and Sudan. Amongst this archaeological archive material are thousands of glass plate negatives from excavations at sites such as Abydos, Deir el-Bahari, Armant, Meir, Amarna, Balabish, and more. In late 2018, the Society raised over £25,000 thanks to generous donations by our supporters, which allowed a team of staff and volunteers to safely rehouse the final 5000 plates from their current home in filing cabinets into conservation grade storage boxes in order to preserve them for future generations.

The Importance of the EES Glass-Plate Negatives

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, photographic negatives were generated on glass-plates. Film technology during this period was still in its infancy and glass-plate technology provided highly detailed reproductions. Thus, the EES’ Lucy Gura Archive contains thousands of glass-plate negatives from our earliest excavations, including Naville’s 1890s excavation of Deir el-Bahari, up until the excavations at Saqqara in the 1960s.

The glass-plate negatives rehoused during the summer of 2019 are from the EEF/EES excavations predominantly at Abydos and Armant, but also a few smaller collections from Meir, Tell el-Amarna, and Balabish.

The EES at Abydos

The EES has a long history of work at the vast and varied Upper Egyptian site of Abydos. The large sub-archive of Abydos material at the EES reflects the nearly 100 year span of work at the site and includes thousands of glass-plate negatives.

Similar to many other excavations in Egypt, the EES’ work at Abydos began with Flinders Petrie who first started working at the Umm el-Qaab area of Abydos in 1899. Auguste Mariette and Émile Amélineau had already identified Umm el-Qaab (meaning ‘Mother of Pots’ due to the vast quantities of surface potsherds) as the location of the Early Dynastic Period royal burials.

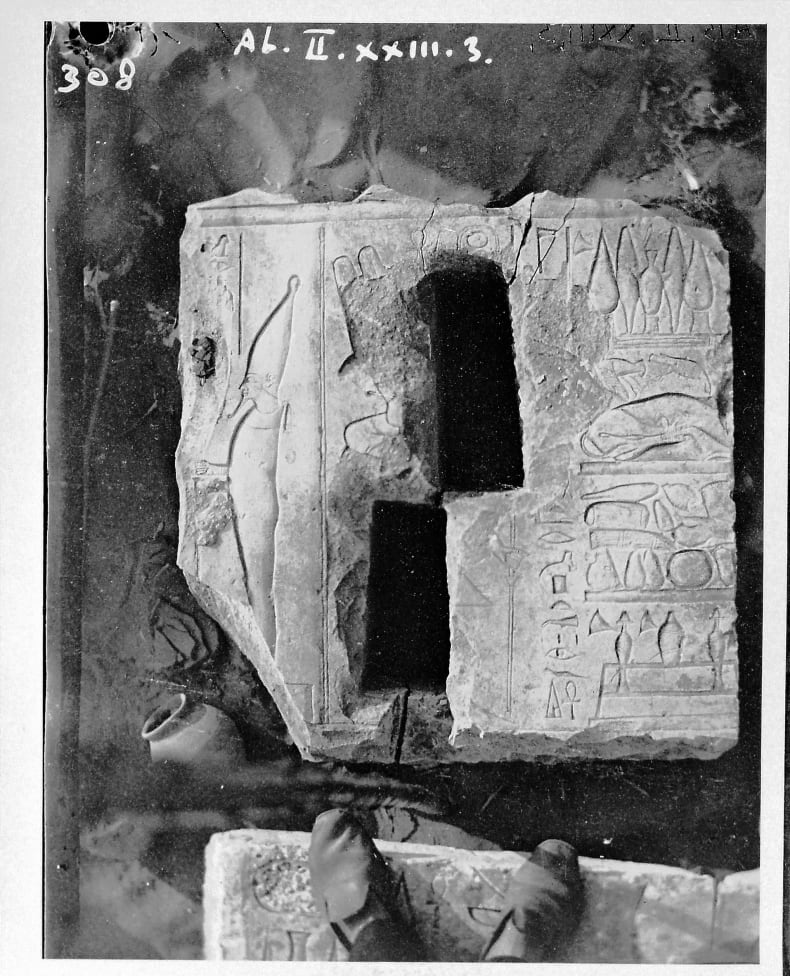

Petrie can be identified as the photographer of this image, thanks to the presence of his ‘Turkish slippers’ seen at the bottom of the frame (AB-II.NEG.308).

While clearing the Tomb of King Djer, Petrie discovered a linen wrapped arm stowed in a niche that had survived the looting and fires that had ravaged the tomb. Petrie unwrapped the arm and took a photo of the remains, which were draped in elaborate bracelets. After giving the arm to Maspero (the head of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo at the time), Petrie was dismayed to learn that the arm had been discarded by the museum in favour of keeping only the bracelets (JE 35054). Therefore, this photograph (as well as a few small fragments of the resin soaked linen bandages now at the Petrie Museum, UC35716) is all that remains of possibly the earliest evidence for royal ‘mummification’ in Egypt.

The ‘arm of Djer’ found by Petrie in 1901. Unfortunately, this photograph is all that remains of the entirety of this find (AB-RT.NEG.II.005).

Petrie later moved to the ancient town site of Abydos called Kom el-Sultan. Here is where one of the most famous discoveries was made - the 7 cm tall ivory statuette of the pyramid builder Khufu, currently on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (JE 36143).

Abydos has long been linked with the cult of Osiris, in fact, the tomb of Djer was long considered to be the burial of the god. In 1901, Petrie first discovered a monument behind the temple of Seti I which he called the Osireon based on accounts of classical travellers, such as Strabo.

This photograph shows the beginning of the clearance of sand and rubble covering the structure on the 9th of January 1914 with the walls of the Seti I Temple in the background (AB.NEG.13.013b).

Work resumed at the Osireon in 1912 by Naville who worked to clear the full substructure. However, it was not fully cleared until 1925 under the direction of Henri Frankfort and Herbert Felton using a water pump to remove the groundwater in the temple. The Osireon is still visible at Abydos; however, shortly after the groundwater was drained from the structure, it refilled and has remained so since.

The large main chamber of the Osireion after it was cleared in 1925. The chamber includes a space for an inset sarcophagus and canopic chest to symbolically represent the burial of Osiris. Around the platform was a moat filled with groundwater and trees planted at ground level mirroring the primordial mound (AB.NEG.25.011).

The EES at Armant

The small Upper Egyptian modern town of Armant is surrounded by a wide array of archaeological monuments – this region includes the ancient city of Hermonthis, dedicated to the god Montu. The region of Armant was excavated by the EES in the 1920s and 30s.

In the spring of 1926 while excavating the Theban tomb of Ramose, Sir Robert Mond, a British chemist with a passion for Egyptology, was told about a bronze bull and inscribed stonework by his rais Moussa Abdel Maluk and Sheikh Omar at a site near Armant that was subject to looting during the first world war. Mond, excited by the prospect of finding the burial place of the Bucchis bulls of Hermonthis hurried south. He was joined by Emery for the first seasons to create a large survey of the region during which Emery discovered a large necropolis on the desert edge.

The team initially discovered the burials of the mothers of the Buchis bulls. The site became an EES concession in 1929 and employed Henri Frankfort and later William Green and Oliver Myers to assist in the location and later excavation of the Bucheum, the burials of the Bucchis bulls themselves.

A monumental Bucchis bull sarcophagus with an offering table and stela (ARM.NEG.0133).

Within the Bucheum, the team, led by Mond and Myers at this point, discovered the mummies and monumental sarcophagi of the Bucchis bulls, along with offering tables and stelae dedicated to the bulls. Very little of the Bucheum is visible on the surface today and much of the ancient remains of Armant have been lost due to encroachment or have been reburied.

Click here to read Alix Robinson's account of the rehousing process.

Impact

This project has had a tremendous impact on the EES’ collections, staff and volunteers, peers of the EES, researchers and more. The funds raised allowed us to employee an archive assistant to oversee the project as well as a conservator to provide training for staff, who in turned trained seven volunteers, as well as staff from the Palestine Exploration Fund and Petrie Museum.

Most importantly, the Society has now safely rehoused over 5000 glass plate negatives allowing the preservation of this invaluable resource for researchers in years to come.

Further Reading:

The Objects Behind the Glass-Plate Negatives

How can you support work in our collections?

If you would like to support the Society’s Collections, then please consider donating here. Funds generated will go directly to providing conservation and care, and improving access to our collections and will be kept in a restricted fund for this purpose.

This Collection Highlight is an extract from:

S L Boonstra and A Robinson, 'Rehousing the EES Glass-Plate Negatives', Egyptian Archaeology 55: 44-47.

See the entire article in Egyptian Archaeology 55.