Moving beyond national narratives: the EES Committee Minutes.

William Carruthers, a recipient of the Society's Centenary Award in 2009-10 and a regular visitor to the Society's archives, is now pursuing doctoral research into the history of Egyptology in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. Here, Will explains how the records of EES Committee meetings can reveal the influence of certain individuals and institutions on the development of our subject.

Histories of Egyptology can suffer from their narrowness. Whilst not always true, it is simple to find Egyptological histories at the national level, or ‘heroic’ biographies of prominent figures in national Egyptological discourses. In the history of British Egyptology, for example, Petrie is often seen as a heroic figure. My research seeks to move beyond such narratives. Whilst I am looking at certain prominent figures – Walter Bryan Emery (1903-1971), at one time the EES’ Field Director and a so-called ‘giant’ of British Egyptology, amongst them – it is clear that their careers are not simply embedded in national contexts.

I spent two weeks recently in the EES’ Lucy Gura Archive researching the Society’s Committee Minutes. The Minutes – held in a number of volumes and dating from the Society’s inception – are an extremely valuable aid in understanding why it is necessary to examine Egyptology as a transnational discipline, even if this situation is not immediately obvious.

When he is first mentioned in the Minutes, for example, Emery’s fortune is clearly in the control of the EES Committee, a national body. On July 6th 1923, discussing the Society’s forthcoming field season at Amarna, this Committee included figures clearly connected to the British establishment. They included Sir John Maxwell, not only formerly in command of the British Army in Egypt, but also Governor of Nubia and Omdurman (and later responsible for the suppression of the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland). Alan Gardiner, another so-called ‘giant’ of British Egyptology and a product of Charterhouse and Queen’s College, Oxford, was also amongst the Committee members.

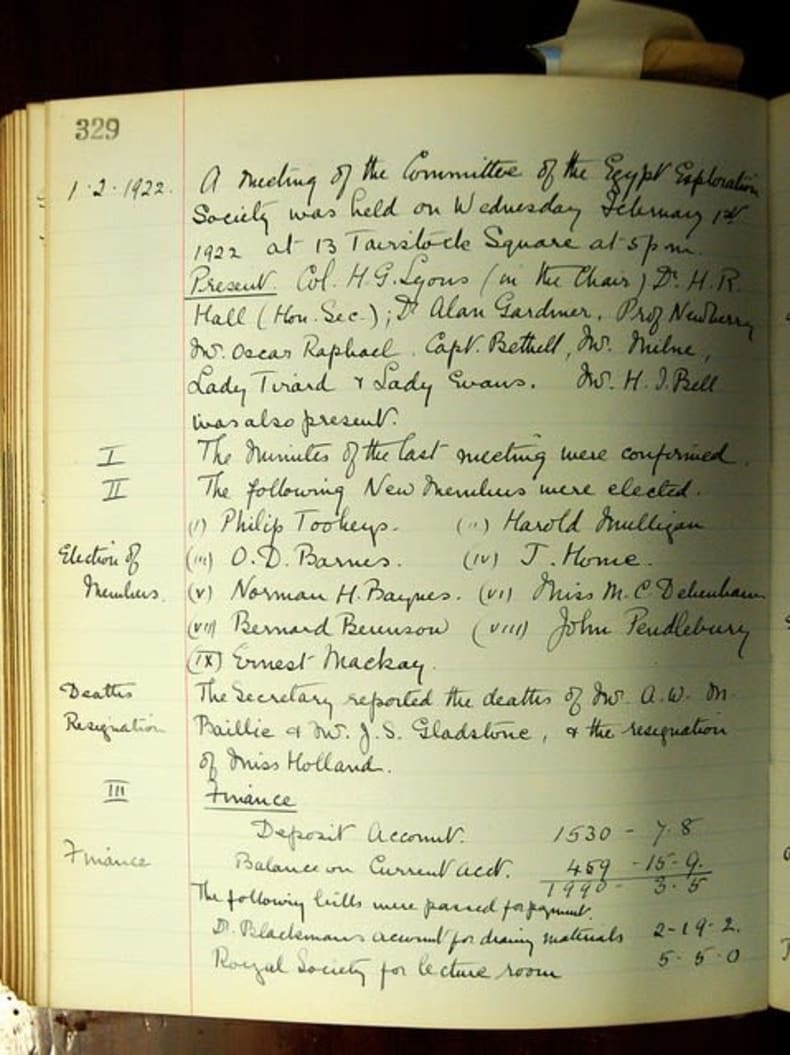

Minutes of the meeting of 1 February 1922 which note that among those present were the well-established Egyptolgists H. R. Hall of the British Musuem, Alan Gardiner, and Percy Newberry, by then retired Professor of Egyptology at the University of Liverpool. Note also that at this meeting John Pendlebury, later Director of Excavations at Amarna but then still a student at Cambridge, was elected a member of the Society along with the archaeologist Ernest MacKay.

These eminently British men (the committee included a sole woman, Lady Helen Tirard, translator of Erman’s Aegypten und aegyptisches Leben into English) directed Henry Hall – of the British Museum, no less – to write to Thomas Peet, Brunner Professor of Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, to enquire whether Emery could join that winter’s expedition. So far, so British – despite Tirard’s translation.

Yet, simultaneously, it is possible to argue that viewing this situation as part of a national narrative is disingenuous. During the same meeting, the EES accepted donations from a Mr. G. D. Libby on behalf of the Toledo Museum of Art, and a Miss Scripps on behalf of San Diego Museum. Financially, Emery’s prospects were as much linked to American donors as they were to any decisions made at the level of a national Committee; without that money, the EES could not do its work.

Of course, this conclusion is hardly revolutionary. It is common knowledge that the EES had, for a long time, an American Branch (eventually wound up after World War Two for financial reasons), and it is clear from excavation reports that the Society had international backing and supporters, as remains the case to this day. However, it is odd that this factor is not taken into consideration when discussing national Egyptological narratives – one might think that nations acted as impenetrable entities when, in fact, the situation was far more fluid.

Throughout the almost 50 years during which Emery was connected with the EES, for example, American association with the Society was constant. Interactions with the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago over the publication of The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos (see earlier article here) stretch to at least the mid-1960s (long after the EES American Branch had ceased to exist). These interactions are a constant, systematic, conversation in the Minute books; other countries are also represented in them.

The EES Minutes are a reminder that Egyptology cannot simply be placed into national brackets. Systematic transnational connections, sustained over decades (and perhaps even centuries), have helped to produce Egyptological knowledge – on the ground, such as Emery’s fieldwork at Amarna, or in published volumes discussing Egypt, such as those related to Abydos. A transnational network of entanglements have, therefore, systematically impacted from afar upon Egypt itself, and disentangling them will help to understand Egyptology’s relationship with the country.

Front cover of the minute book for 1915-27