Peet, the JEA and the First World War

by Clare Lewis

This year the Society celebrates the 100th volume of The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. It is also a time to reflect on the centenary of the start of the First World War. In this short article Clare Lewis looks at these two moments in history and the important figure in the history of Egyptology, Thomas Eric Peet.

When the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Society) launched the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology(JEA) in January 1914 few could have realised that less than seven months later Britain would be immersed in a conflict that was to result in millions of deaths. With the centenary of the First World War upon us, here I want to consider one Egyptologist whose career, intertwined with the EES and the JEA, was, like so many others, affected by the hostilities that ensued.

Thomas Eric Peet (1882-1934) was a highly influential figure in the history of British Egyptology and its formation as an academic field but has been somewhat overlooked. Having first concentrated on Italian prehistoric archaeology he began to work for the EEF in 1909, and by 1911 was devoting all his time to Egyptology. From 1909-1913 Peet excavated on the EEF digs at Abydos, firstly with the Swiss archaeologist Édouard Naville (who had worked for the EEF since its inception in 1882) and then independently. Differences in excavation approaches and publication aims, and in particular Peet’s desire for more scientific methodologies, caused increasing animosity between the two men. Thus, in the first edition of JEA two separate articles appear on Abydos, one by Naville (1914: 2-8) and one by Peet (1914: 35-9).

1914 was supposed to mark a decisive year for the EEF. Restructuring had been underway through 1913 and the launch of the JEA, as part of this effort, transformed the way that the EEF communicated with its subscribers. Previously dig reports had been sent to subscribers in return for their donations. Through the launch of the JEA dig reports were freed to become “models of scientific authority” (see Gange 2013: 153-5) and with this in mind, subscribers became members, who were to receive, for their membership dues, the JEA, whose aims were announced in its first editorial:

[To] give all information obtainable regarding excavations that are being conducted in Egypt, and will contain articles, some, specialized and technical, intended mainly for experts, others, simpler in character, such as will be intelligible for all who care for Egypt and its marvellous interests.

The outbreak of the First World War was to limit this scope for the next five years. Nevertheless the JEA continued to be published throughout the hostilities, despite the cessation of all EEF excavations in Egypt from 1915 until 1920/1.

The Committee books and correspondence held in the EES archives show that the Fund’s Committee also continued to meet during the war. The time was used to carry on the reorganisation of the Fund, which would be renamed the Egypt Exploration Society in 1919, and discuss its scheme of work after the War and how the objectives of the Fund should be reshaped to explicitly “promote the knowledge of Ancient Egypt and the Science of Egyptology” (EES.XVIII.32). By 1915, as part of this process, Peet had not only been identified as the successor to Naville as the prospective lead excavator for the Fund: “[in] considering returning to active operation then Peet is the man” (EES.XIV.c), but also as a potential future editor of the JEA.

Peet in the uniform of the 14th Battalion King’s Liverpool Regiment. Courtesy of the Peet family, copyright: Clare Newton

However, Peet had other ideas. In 1915 with signs that the War was escalating, and fiercely patriotic, he signed up despite the attempts of friends and colleagues to get him into administrative work in Britain. He received his commission in October 1915 and went on to serve first in Salonika, and then on the Western Front as a Lieutenant, King’s (Liverpool) Battalion.

Keen not to lose Peet from Egyptology, a memorandum was drawn up by the EEF in November 1915 (EES.XIV.c) in which Robert Mond, Alan Gardiner and the EEF formally agreed to contribute to his army salary to maintain it at a pre-defined level, in effect paying him what they understood to be a retaining fee throughout the First World War.

Still concerned by the threat of losing Peet after the War, correspondence shows that Gardiner (by then editor of the JEA) continued to engage Peet in Egyptology. For example, Peet wrote in 1918 to Percy Newberry, his then mentor that:

of Egyptology I know nothing except the Eg. Journal [the JEA] which Gardiner sent out to me regularly. He keeps it up to an excellent standard under these difficult conditions.

Furthermore after he transferred to the Western Front Peet observed, “reading is mostly restricted to pamphlets which can be thrown away as read”. However welcome the JEA was during this time, in 1920 he was to convey to Newberry the problems its editorial stance during the war had created:

When in France I had some copies of our Journal with me, and two brother officers who looked them over both made the same comment. For they both asked me how my paper could on one page appeal for subscriptions and on the next print obituaries of slain Germans with, and this was the point, expressions of regret for their deaths.1 I had no answer. Now these men were not fools, but rather typical British readers, and what occurred to them has, as I have heard more than once, struck and offended other readers. The irony of it to people whose sons and husbands and brothers were in the trenches was a little too fine to be relished.

On his return from the First World War, Gardiner believed that the retaining fee meant that Peet was destined to work for the EES. However, concerned that the Society could not provide him with the steady income he sought, Peet refused to relocate, believing that he had been paid a salary through the War, rather than retaining fee, and that his commitment to the EES had been honoured through publication. The ensuing impasse was resolved by Newberry resigning his Chair at Liverpool University in Peet’s favour. Commitments for this role rose and Peet’s increasing focus on philology meant that the 1920/1 season at Amarna became the last excavation that Peet was to undertake for the EES. Once more Peet explained this decision in 1920:

I always intended to try to give up regular excavation at 40 or thereabouts. The war and circumstances have hastened the moment.

However, he was persuaded to take up the editorship of the JEA by Gardiner. He was to be editor from 1923 to his death in 1934 and his reviews of over 91 publications over his tenure were, in part, responsible for building up the EES’s extensive library. Over the duration of Peet’s tenure at Liverpool, Gardiner emerges as an increasingly important influence on his career, ultimately securing him a Readership at Oxford in 1933 and providing both the financial stability and platform for the increasingly philological focus that Peet desired (Gardiner 1933). Unfortunately this opportunity was never fulfilled as Peet died five weeks after delivering his inaugural lecture in February 1934.

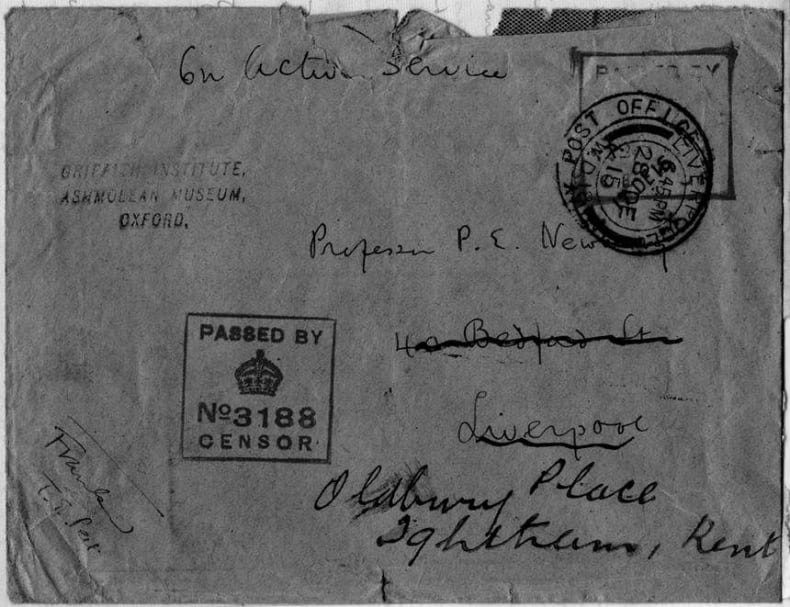

Envelope from Peet at Salonika to Newberry with censor marks. Copyright: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

The archives held at the EES, the Griffith Institute and personal papers which the Peet family have generously shared, combine to give an insight into one man’s career, and how it has been shaped by both war and shifting personal loyalties. This forms an important part of the author’s doctoral research (at UCL) into the development of British Egyptology in academia and the nuances that have shaped its trajectory. This research includes gathering all extant examples of Egyptological inaugural lectures given at British universities.

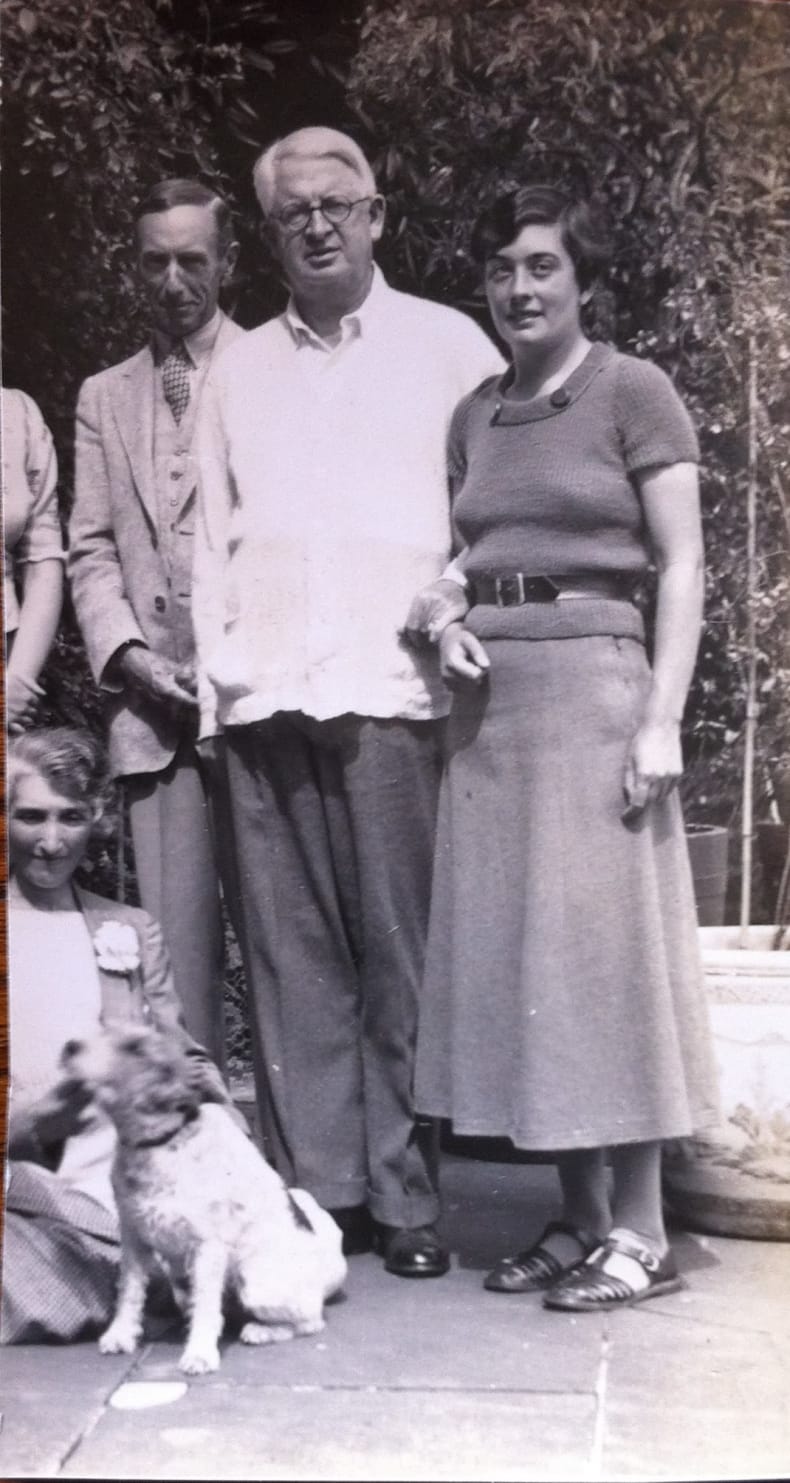

Peet, Gardiner, and Peet’s daughter Patricia shortly before Peet’s death. Courtesy of the Peet family, copyright: Nicholas Postgate

1The German obituary referred to above appears to relate to the son of another famous Egyptologist, Adolf Erman, under whom Gardiner had studied in Berlin from 1902-1912. Whilst today this obituary might be viewed as forward thinking, it needs to be explored carefully within the context of the heightened patriotism and personal sacrifice of the time.

Further reading

Gange, D. 2013. Dialogues With the Dead: Egyptology in British Culture and Religion, 1822-1922. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Naville, E. 1914. ‘Abydos’, JEA 1: 2-8.

Peet, T.E. 1914. ‘The Year’s Work at Abydos’, JEA 1: 37-39.