Henry Villiers Stuart's Nile Gleanings

by Hazel Gray

A previous collection highlight introduced the explorer James Bruce, son of a Scottish laird, but the wealthy and leisured from many countries were drawn to Egypt in the 18th and 19th centuries. This article will explore the book Nile Gleanings by Henry Villiers Stuart, son of the Irish Baron Stuart de Decie, another addition to library stock from the recent Walker bequest. It is a particularly welcome addition since Villiers Stuart was a member of the provisional committee which pushed forward the foundation of the Egypt Exploration Fund, and is mentioned in that capacity in a letter from Amelia Edwards dating to 22 July 1883 now in the EES archive.

A portion of a letter from Amelia Edwards to her co-founder Reginald Stuart Poole in 1883 mentioning a 'Mr Villiers Stuart' as a committee member (COR.003.a.02).

Henry Windsor Villiers Stuart was born in 1827. He served in both the Austrian and British armies before studying Classics at Durham University, and made his first visit to Egypt in 1849, whilst still an undergraduate. After graduation, he was ordained into the Church of England, and served as vicar until 1871, when he resigned to pursue a career in politics. Though he inherited his father's estate on the baron's death in 1874, he did not succeed to the title, as there was doubt over the legality of his parents' marriage. He travelled extensively, including several trips to Egypt, but also to South America and Barbados. He published several works on ancient and contemporary Egypt, being commissioned by the British government to report on the conditions there after the British military intervention in 1882. He died in 1895, when he slipped whilst disembarking from a boat, fell into the river and drowned.

Nile Gleanings (full title: Nile Gleanings, concerning the Ethnology, History, and Art of Ancient Egypt, as revealed by Egyptian Paintings and Bas-Reliefs. With descriptions of Nubia and its Great Rock Temples to the Second Cataract) records a visit to Egypt and Sudan in 1878-79 by Villiers Stuart and his wife, and was published shortly after their return. The expressed aim is to avoid reporting places and monuments which have been published before, to describe purely from personal observation, and to offer sketches made on site. This book is thus richly illustrated by Villiers Stuart's own drawings (initialled ‘HVS’).

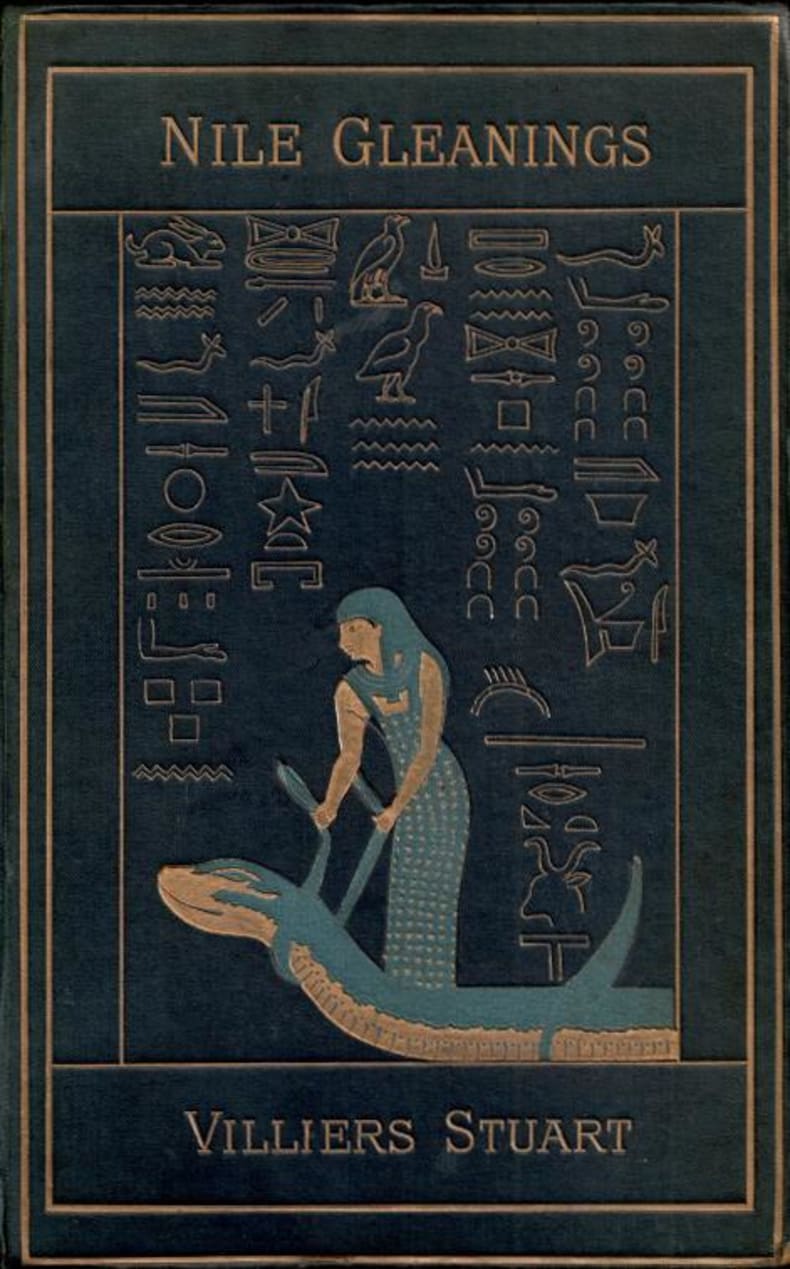

The illustrated cover of Villiers Stuart's Nile Gleanings first edition

The couple took a dahabiyeh south from Cairo, visiting numerous sites along the way, and he describes the various expeditions vividly, sharing both the adventurous nature of contemporary tourism in Egypt and serious consideration of the ancient monuments and their state of preservation.

Here, for instance, he recounts the perils of a visit to the Crocodile Caverns of Gebel Aboufaida:

‘After about an hour's ride across this desert we came to an insignificant-looking cleft in the surface – this was the entrance to the cavern. The four guides... each entered with a candle and a dagger (the latter was to cut up the mummies with)... We noticed that the rocks were covered with a sticky, greasy, black deposit, like tar. Our guides informed us that this had been caused by a fire which had occurred in this singular depot of departed reptiles. A party of travellers had entered, and soon after a volume of smoke came rolling out from the pit which forms the ante-room to the caverns. Some sailors who had accompanied the party, and who were awaiting their return outside, tried to penetrate, but found the smoke so suffocating that they had to abandon the attempt. Neither the unfortunate explorers nor their guides were ever seen again... It was surmised that they may have lighted their cigars as an antidote to the bad air, and that in doing so a spark may have fallen amongst the mummy rags that litter the floor, dry and inflammable as tinder… At last we emerged into a chamber about fifteen feet across, and high enough to stand up in... Igniting some magnesium wire, the brilliant light fell upon such a scene as Dante never dreamt of for his Inferno... the strange weird forms of the reptiles, with their long snouts displaying rows of sharp white fangs, the grinning human heads (many with all their hair still on), thick curly hair, and white gleaming teeth and hollow eyes, that seemed to reproach us for disturbing their rest, the litter of grave clothes, the shrill complaining cry of the bats, as they flew hither and thither, and then then the dark shadows of the recesses that opened on all sides and had served to store the mummies in – all this formed an experience never to be forgotten, and scarcely to be surpassed by the wildest nightmare.’

He emerged from this adventure with a selection of crocodile mummies and one human mummy, stripped of its bandages. Villiers Stuart amassed a collection of Egyptian antiquities on his many visits to the country, keeping them at his home in Dromana. In 1921, the collection was loaned to the National Museum of Ireland, but unfortunately later removed and sold at auction. I have not been able to establish whether the human or crocodile mummies from Gebel Aboufaida were part of the collection, but they may have suffered the same fate as others collected by Victorian travellers – being thrown overboard when the smell became overpowering!

From Villiers Stuart's account, it appears that travelling in Egypt and Nubia was fraught with danger. Whilst in Nubia, he reports that:

‘We met a dahabeeah being towed by a steamer; on enquiry, we heard that one of the gentlemen had nearly shot his foot off while out after crocodiles, and was hurrying back to meet a surgeon, whom he had telegraphed for to Cairo; we heard that the foot would have to be amputated – a sad ending to a pleasure trip.’

And again, when at the First Cataract:

‘A number of... Nubians advanced, each carrying a log of wood, bestriding which, they boldly pushed out into the roaring, seething waters, and were presently hurried along at the rate of at least fifteen miles an hour down the rapids. They guided their logs with their hands, sitting their wooden steeds magnificently, never allowing them to turn or spin around, and keeping an upright position throughout... They rode the furious torrent with so much ease and grace, that it seemed as if anyone could do. Some time ago a young Englishman undertook to achieve the same feat, but the angry cataract crumpled him up and beat him to death in a moment.’

But among all the breathless adventures, Villiers Stuart was investigating and recording the ancient monuments in a much more serious manner. Near Dakkeh (Dakka), in Nubia, he found the remains of a temple, and translated the hieroglyphic text on a stele of Thutmose III.

‘This stele was partly buried in the ground, and the inscription was underneath, turned upside down; it had only just been unearthed, and thanks to the friendly sand it was in so perfect a state of preservation that even the blue paint still showed in the hieroglyphics.' He contrasted this with the treatment of another stele from the same area – and here you can hear clear echoes of the warnings of Amelia Edwards written a few years earlier.

'We also saw a stele with a long inscription and a cartouche no longer legible, but which a few years ago still displayed the oval of Amenemhe[t] the Third of the twelfth dynasty, i.e., 4800 years ago. This stele is of great historical interest; it mentions the eleventh year of the reign of this ancient king, and it is a great pity that it should have been so maltreated; the inhabitants of the neighbouring village have unfortunately discovered that it makes a capital grindstone, and they now grind all their tools upon it; fully half the inscription is thus already destroyed, and the remaining half will soon follow. It is much to be deplored, when these monuments have been so wonderfully preserved through all the long centuries during which they were sealed books to mankind, that now, when at last we have found the key and have power to decipher their revelations, their destruction should proceed at such an alarming pace.’

The highlight of the trip for Villiers Stuart was that he claimed ‘the good fortune to discover a hitherto unknown tomb, which casts an important light upon an obscure period of Egyptian history’. This is a tomb that will be known to many who have visited Luxor – that of Ramose, TT55.

‘While poking about at the base of a rock, half buried beneath an avalanche of quarry rubbish, I espied a portion of the globe, or radiating disk, which figures so often at Tel-el-Amarna, and set a crew of natives to clear away the debris. I discovered it to be a tomb which reproduced the peculiarities hitherto supposed only to be found at Tel-el-Amarna, but the execution was infinitely superior; the sculpture was in very white limestone... On one side of the entrance was represented Amunoph [Amenhotep] the Fourth and his queen, beneath a canopied pavilion... On the other side of the portal we Khou-en-Aten [Akhenaten] and his queen. The former is a most peculiar-looking man, with a very long chin and long nose, with a slight thin figure and an effeminate look; he could never have been an Amunoph, but his wife resembles Tai-ti [Tiye], the wife of Amunoph the Third, and I suspect that the true explanation of the mystery that hangs over this curious episode in Egyptian history, of which her husband is the hero, is that she was the daughter and heiress of Amunoph the Fourth, and married a foreigner, Khou-en-Aten,who reigned in right of his wife. The queen of Amunoph the Fourth bears the name of Nofre-ti-ti [Nefertiti]... The queen of Khou-en-Aten bears the name Nofre-nofrou-nofre-ti-tai-Aten [Neferneferuaten Nefertiti]. Not identical, at the same time that they just present the resemblance that might be expected in the names of mother and daughter... The tomb we saw at Thebes at all events conclusively proves that the singular looking personage who figures on all the tombs at Tel-el-Amarna is not identical with Amunoph the Fourth, for as I have already said, on one side of the portal is Amunoph the Fourth, with his wife standing behind him, and without the Aten disk over his head, or anything else to distinguish him from other Pharaohs. On the other side is Khou-en-Aten, with his wife seated behind him, and with the distinctive titles of royalty.’

An interesting attempt to analyse the images in the tomb, and the tomb's discovery was considered in a review of the book in Nature as 'the principal new point of the work, and is the one new and important contribution to the obscure history of the heretical division which took place about the thirteenth century B.C.' We now know that Amenhotep IV and Akhenaten were one and the same, and that the construction of the tomb spanned the pre-Amarna and Amarna periods of Akhenaten's reign, and hence is decorated in both traditional and Amarna styles, though it remained unfinished.

|

|

Each side of the entrance of the Tomb of Ramose (TT55) showing pre-Amarna style and Amarna style art (H Gray)

Villiers Stuart continued to visit Egypt and to publish works on the country's history – The funeral tent of an Egyptian queen (1882) – and its current situation – Egypt after the war (1883 which also covered latest archaeological discoveries and noted damage to some of the sites he had visited in 1879) and Reports by Mr. Villiers Stuart respecting the progress of reorganization in Egypt since the British occupation in 1882 (1895). On a visit in 1882-83, he discovered the alabaster altar and basins at Niuserre's sun temple at Abu Ghurab, He remained a member of the Egypt Exploration Fund's Committee until his death, so we are grateful to be able to add one of his works to our library.